This is a summary paper, which provides background material on Iran’s nuclear activity, and the policy options to address this challenge.

The stated intention of the Biden administration to re-enter the original Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA) has triggered a heated policy debate. Some of the more critical voices come from Israel and other key actors in the Middle East such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, who are directly and strategically threatened by Iran. These countries have no doubts that Iran never abandoned its ambition to become a nuclear-armed state; that the JCPOA left open pathways for the realization of this ambition; and that a nuclear Iran would pose a critical threat to Israel and the region.

Iran’s JCPOA Violations

Over the past year and a half, Iran has gradually encroached on its commitments under the JCPOA. The EU and the E3 have expressed serious concerns about these Iranian breaches and have called on Iran to reverse them while stopping short of taking punitive action.

According to Israel’s intelligence assessment, Iran’s break-out time (for accumulating sufficient military-grade fissile material for a bomb) has shrunk to four months, nearing the levels reached before the JCPOA. Iran would require 21-24 months to construct a nuclear weapon in parallel with enrichment, assuming there is no active weapon program.

JCPOA Critiques

The main critique of the JCPOA is that it does not properly cover all key dimensions of a nuclear military program, including fissile materials, delivery systems and weaponization, and does not guarantee fool-proof inspection and verification. Specifically:

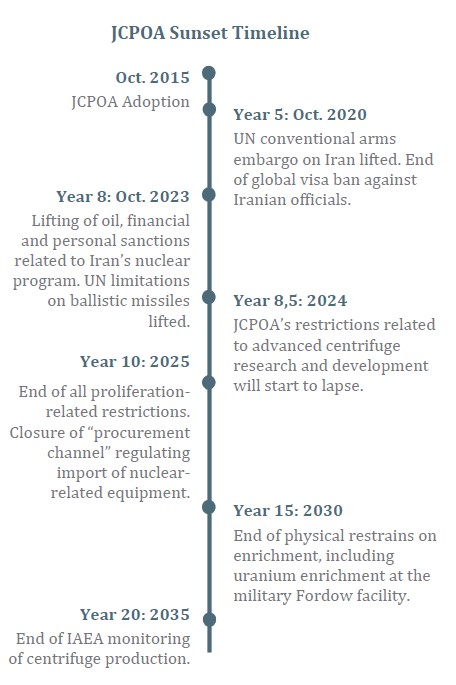

- The sunset clauses lift most limitations on Iran’s ability to deploy advanced centrifuges and enrich uranium on an industrial scale to higher levels within 10-15 years of signing (2015).

- Missiles, which are the main delivery systems for a nuclear device, are not covered by the JCPOA but rather by a weakly-worded UN Security Council Resolution (2231), which is open to interpretations and set to expire in October 2023.

- The file of Possible Military Dimensions (PMD) was closed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in December 2015, notwithstanding damning IAEA reports on Iranian nuclear activities of a military nature. The seizure (2018) by Israel of the Iranian nuclear archive shed further light on Iran’s nuclear military program, calling for the reopening of the PMD file.

- The inspection and verification regime has proven deficient in terms of short-notice challenge inspections of undeclared, suspected sites (especially military sites) and the questioning of related personnel.

- In addition, the 2015 JCPOA baseline to which the parties are supposed to return has not remained static. Iran’s subsequent development of know-how (especially as pertains to centrifuges and missiles) significantly shortens Iran’s timetable for reaching the nuclear threshold, even if it goes back to compliance.

Those who criticize returning to the JCPOA therefore believe that this move would reinvigorate a fundamentally flawed deal while enabling an unmoderated, emboldened Iran to advance its nuclear knowhow, as it approaches the JCPOA’s sunsets.

Policy Options

- Reviving the Iran nuclear deal by going back to its original terms and then striving to make it “longer and stronger.” This plan implies that the new U.S. administration acknowledges flaws in the deal but believes there is no better way to roll back Iran’s accumulating violations of the JCPOA. The big policy question is whether the U.S. and its European allies will master sufficient political will to ratchet up pressure on Iran once it is back into compliance with the JCPOA and refuses to move to an enhanced deal. Regional actors are doubtful.

- Applying “Maximum pressure” against Iran until it is compelled to revise its position and agree to negotiate a new and improved deal that fixes the original flaws. The policy question is what are the chances of continued “maximum pressure” to yield the desired results without escalating to a violent confrontation.

- Reaching an interim agreement that would trigger a partial lifting of sanctions in return for certain Iranian concessions. This middle option would reduce Iranian violations while retaining some leverage on Iran, which could serve as a basis for an improved agreement.

Given that Israel sees a nuclear-armed Iran as a threat of potential existential dimensions, it believes it must retain a military option as a last resort. Israel’s definition of a “red line” in this context focuses on Iran’s ability to acquire a nuclear weapon with a short breakout time.

Recommendations

- Iran is playing a dangerous game of brinkmanship and “maximum pressure” of its own. In preparing for restarting negotiations alongside the U.S., Europe should seriously consider the critiques of the JCPOA, consult with key regional actors who are directly threatened by Iran, and take concrete action. For diplomacy to succeed in effectively blocking Iranian pathways to a nuclear weapon, it must be backed by robust disincentives, including a viable and credible military option.

- Ideally, Iran should be denied an indigenous enrichment capability, including mastering the fuel cycle. Unfortunately, this option may not be realistic at this point. The practical approach should therefore focus on extending the sunset clauses for decades and establishing an intrusive “anytime, anywhere” inspection regime. In addition, Europe should call for banning the development of sophisticated centrifuges, addressing dangerous dimensions of Iran’s missile program and reopening the PMD file.

- The nuclear file is most critical and should not be overloaded. Hence, Iran’s regional activities should be addressed as a separate issue.